In the past years, there has been increasing awareness by the public and policy makers on the potential harm that social network manipulation can produce. Yet, most researchers have looked at the front end of the problem: developing algorithms to flag fake accounts on social networks and suspend them. No studies have investigated the problem from an industry perspective, with questions such as:

In the past years, there has been increasing awareness by the public and policy makers on the potential harm that social network manipulation can produce. Yet, most researchers have looked at the front end of the problem: developing algorithms to flag fake accounts on social networks and suspend them. No studies have investigated the problem from an industry perspective, with questions such as:

- How political campaigns or hate groups manage to share 100,000 times their posts ?

- Where do they buy such service?

- How is the service delivered?

Of course, there are many possible answers: from asking script kiddies, to using click farms or even by relying on politically coordinated efforts. Yet, there is also a synchronized market that exists where one can buy such service. Many people from the entertainment industry were caught purchasing fake followers on such market, also known as the market for social media fraud (SMF).

Social media fraud is the process of creating likes, follows, views, or any other online actions on OSN [Online Social Networks], to artificially grow an account’s fan base.

This study uncovers the different actors involved in the supply chain behind the SMF market. This was possible due to an ongoing investigation of an IoT botnet, named Linux/Moose, involved in the production of that service. The details of the study are presented in a research paper published in the proceedings of the Virus Bulletin conference, taking place in Montreal on October 3rd and 5th, 2018. The findings are summarized below.

The industry’s supply chain depicts the flow of production for a good or a service.

The Botnet’s Production Process

At the lowest level of the supply chain, the production of millions of fake accounts to conduct SMF requires automation, which can be done through a botnet, like Linux/Moose. This botnet is known to infect Internet of Things (IoT) devices and use them as proxies to conduct SMF.

By investigating the botnet’s traffic through the honeypots we set up, we found that seven whitelisted IP addresses could use the network of infected (IoT) devices to send requests on social networks. These seven whitelisted IPs could have represented a model in which seven -or fewer- actors could log in and use the infected devices to conduct SMF. Yet, this was not the case. We rather found that these whitelisted IPs are set up for fake accounts management. They are all are running Windows Server and exposing RDP for remote management, and although each whitelisted IP address manages a set of fake accounts, there is an overlap in the accounts being followed by the botnet (the potential customers of SMF).

This leads us to think that a rather sophisticated proxy-aware Instagram fat client is used to manage the fake accounts and the flows of interaction with Instagram. Confirming the exact fat client that is used by this actor will, however, require further research.

Reseller Panels

Investigating Linux/Moose’s traffic leaked one of the botnet’s most important partners: reseller panels, which are panels that sell social media fraud in bulk, at a cheap price. They look like the web capture presented in Figure 1.

These panels provide application program interfaces (APIs) for managing orders and receiving them. This means that reseller panel owners can connect their own panel to a botnet via a sending API and receive their orders from other panels via a receiving API, thus acting as a middleman.

Interestingly, through forum inquiries, we found that reseller panel owners have a hard time finding a botnet to which connect their panels. They often ended up just connecting to a cheaper reselling panel, as mentioned in the web capture presented in Figure 2. Botnet operators, due to the illegality of their activities, may wish to keep a low profile and only deal with a small number of trusted partners.

Moreover, through our investigation, we found that most panels were alike, even almost identical. Simple clustering analytics showed 66% of our sample of 343 reseller panels were coded in PHP, used similar combinations of client-side JavaScript libraries (including jQuery, Moment.js, Underscore.js, Twitter Bootstrap and Font Awesome) and were hosted on the same IP address belonging to OVH. These panels are related to one actor: a software panel seller.

Software Panel Seller

This actor provides ready to use panels (including hosting) for anyone wishing to get involved in the industry, thus diminishing barriers to entry. Further inquiry led us to find other software panel sellers, offering similar services. They enable thousands of individuals to get involved in the industry without having any technical skills.

Customer-Facing Sellers

Reseller panels sell to customer-facing sellers, which are the ones who sell directly to clients, offering a friendly-to-use website with various payment methods and chat options. These customer-facing websites are easily available through simple online searches, as discussed in a previous study. Figure 3 depicts an example of such sellers.

Mapping the Supply Chain behind the Industry of Social Media Fraud

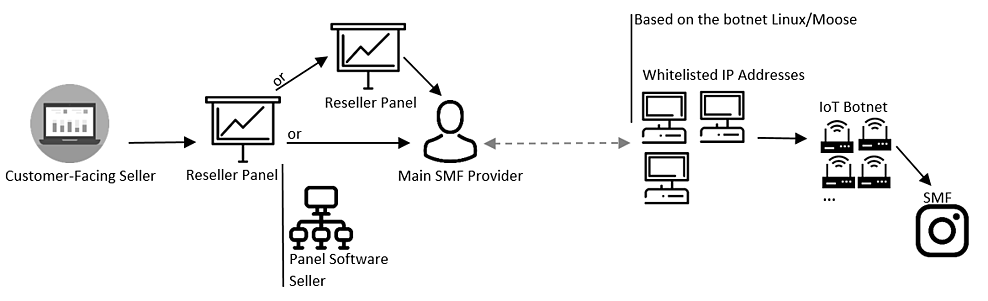

The industry supply chain is summarized in Figure 4. Many actors are involved in the SMF industry, allowing the botnets’ operators to hide behind multiple semi-legit actors.

The New York attorney general opened an investigation on a customer-facing selling company, named Demuvi, last January. Interestingly, the above depiction places this company within its larger industry structure (it was alleged that Demuvi bought their fake followers in bulk through reseller panels). It shows that Demuvi is only the tip of the iceberg and other measures could be undertaken to destabilize this market, such as targeting software panel sellers or reseller panels.

Revenue Division in the Chain

With relevant data, insights on the revenue division within the supply chain can be inferred. Based on this study and a previous study we conducted on customer-facing sellers, we know that the medium price for 1,000 Instagram followers on customer-facing websites is USD 13 and USD 1 on reseller panels, as shown in the Table below.

| Customer-Facing Websites | Reseller Panels | |

| Medium Price for 1,000 followers on Instagram | USD 13 | USD 1 |

Thus, if no other costs are incurred, the customer-facing sellers would make a profit of 12 USD for selling 1,000 followers, leading to a net profit margin of 92%. This means that for each dollar invested, customer-facing sellers would receive a net income of 92 cents, a return on investment that is lofty.

Also, this indicates that main providers, like the operators behind the Linux/Moose botnet, earn a very small amount of money for each follower created and sold. If this industry was legal, SMF providers could integrate vertically and own the whole supply chain, allowing them to absorb the profit margin from other actors. Yet, the illicit aspect of their activity forces them to stay in the shadow and earn less per follower produced.

Interestingly, this finding follows a large criminology literature (having roots in the 1980 with the work of the economist Peter Reuter on the consequences of product illegality on the organization of markets). This literature states that yes, one can make money with crime, but never as much as if one would have done the same business legally. The driving forces of product illegality compel those involved in illicit activities to hide, diminishing their potential revenue.

Those who seem to have an interesting business are the software panel sellers: for every panel they host, they earn a fee per month, ensuring recurring business with their customers. The fee, at the time of writing, was around 25 USD to 200 USD per month, depending on the number of orders completed on the panel. With these fees, few subscriptions are needed to start making an interesting amount of money. For example, hosting 100 panels at a minimum of 25 USD would give a revenue of 2,500 USD per month.

The software panel seller found in our sample hosted 977 domains, which means that the person behind this business may earn a significant monthly revenue.

Conclusion

This research is part of a two-year-long investigation that attempts to place a botnet’s operations in its economic context, understanding the ecosystem in which it evolves. We hope the knowledge produced will be of use to policy makers and researchers willing to curb this illicit industry.

For more detailed information, the research paper will be published in the proceedings of the Virus Bulletin conference, taking place in Montreal on October 3rd and 5th, 2018.