Author: Philippe Arteau

Unicode-related vulnerabilities have seen an increase in momentum in the past year. Last year, a Black Hat presentation by Jonathan Birch detailed how character normalization NFC/NFKC can lead to glitches in URL and host manipulation. Recently, two vulnerabilities were found in password reset functionality. The two affected applications were

Root Cause

Here are few examples where a single Unicode character will be converted to one or multiple characters in the ASCII range.

Python

"\u00DF".upper() => "SS"Java

IDN.toASCII("\u2116dejs.org") => "nodejs.org".NET

new URI("https://faceboo\u212A.com").Host =>

"https://facebook.com"Case Study 1: Oracle HostnameChecker (CVE-2020-14577)

private boolean isMatched(String name, String template, boolean chainsToPublicCA) {

// Normalize to Unicode, because PSL is in Unicode.

name = IDN.toUnicode(IDN.toASCII(name));

template = IDN.toUnicode(IDN.toASCII(template));

[....]

return matchAllWildcards(name, template);The final hostname stored in either name or template will not properly describe the remote host.

| Input | IDN.toUnicode(IDN.toASCII(Input)) |

| U+FF41 a | a |

| U+FF45 e | e |

| […] | |

| U+212A K | k |

| U+2116 ℕ | no |

| U+2121 ℡ | tel |

Approximately 321 Unicode code points are problematic and can cause this vulnerability.

Risk

An attacker could potentially create a malicious certificate or a certificate signing request (CSR) with the Unicode character U+FF41 to create a collision with a domain name that contains an “a”. This is possible because the common name is part of the subject field in X.509 certificate, which supports UTF-8.

In practice, host checking is only one part of the verification, the second being the chain of trust control. It is very difficult to get an Internet Root authority to sign a CSR with a special common name. Unless there is a weak security control on the authorities’ side, it should not be possible.

Two very narrow scenarios are possible to get the required chain of trust:

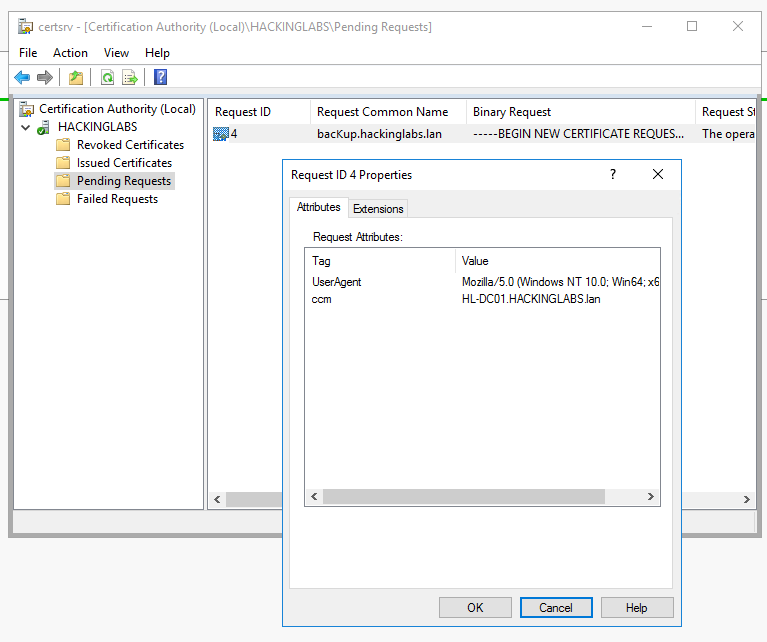

- The targeted client is trusting an internal certificate authority (ie: Windows Server Certificate Authority allows CSR with UTF-8 extended character).

- The attacker has compromised a certificate authority and he is hiding the malicious certificate with Unicode collision., which is very unlikely.

As you can see, this weakness – although hazardous – will not easily allow an attacker to intercept traffic from all Java applications.

Proof-of-Concept

If you want to see the weakness by yourself, we have published the proof-of-concept submitted to Oracle and OpenJDK. It includes the python script to generate malicious certificates.

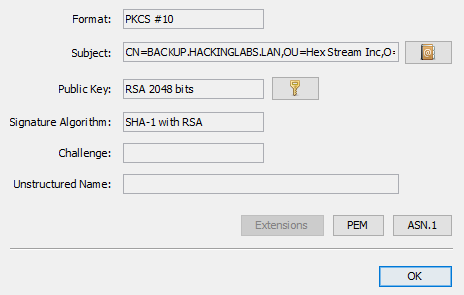

Here is a view of the malicious certificate:

Proposed Solution

Avoiding IDN.toASCII() would solve the problem, as it avoids potential collisions with domains using special Unicode characters.

Timeline

- Vulnerability reported: January 14, 2020

- Acknowledgment that an investigation has started: January 14, 2020

- Fix was released: July 2020

Case Study 2: HTTPClient 4.5.10

In HTTPClient 4.4 and higher, the class PublicSuffixMatcherLoader was vulnerable to improper handling of Unicode encoding (CWE-176). This class is used by the DefaultHostnameVerifier class, which is in charge of verifying the hostname during the TLS handshake.

Deep Dive Into the Code

Looking at the matches() method in the PublicSuffixMatcherLoader class, we can see that it relies on the getDomainRoot() method.

public boolean matches(final String domain, final DomainType expectedType) {

if (domain == null) {

return false;

}

final String domainRoot = getDomainRoot(

domain.startsWith(".") ? domain.substring(1) : domain, expectedType);

return domainRoot == null;

}public String getDomainRoot(final String domain, final DomainType expectedType) {

[...]

final String normalized = domain.toLowerCase(Locale.ROOT);

String segment = normalized;

String result = null;| Input | Input.toLowerCase() |

| K (U+212A) | k (U+006b) |

| İ (U+0130) | i̇ (U+0069 U+0307) |

val verifier = DefaultHostnameVerifier();

val cert = mock(X509Certificate::class.java);

`when`(cert.getSubjectX500Principal()).thenReturn(X500Principal("CN=montrehac\u212A.ca,

OU=Fake, O=Fake, C=CA"))

verifier.verify("montrehack.ca", cert);Risk

This issue found in HTTPClient has similar risks to the previously presented JDK issue. It is however limited to domain names with the letter k.

Fix

You can view the commit made by the HttpClient team for more detail on the fix.

Timeline

- Vulnerability reported: January 9, 2020

- Vulnerability fixed: January 14, 2020

- Release: January 23, 2020

CAS D'UTILISATION

Cyberrisques

Mesures de sécurité basées sur les risques

Sociétés de financement par capitaux propres

Prendre des décisions éclairées

Sécurité des données sensibles

Protéger les informations sensibles

Conformité en matière de cybersécurité

Respecter les obligations réglementaires

Cyberassurance

Une stratégie précieuse de gestion des risques

Rançongiciels

Combattre les rançongiciels grâce à une sécurité innovante

Attaques de type « zero-day »

Arrêter les exploits de type « zero-day » grâce à une protection avancée

Consolider, évoluer et prospérer

Prenez de l'avance et gagnez la course avec la Plateforme GoSecure TitanMC.

24/7 MXDR

Détection et réponse sur les terminaux GoSecure TitanMC (EDR)

Antivirus de nouvelle génération GoSecure TitanMC (NGAV)

Surveillance des événements liés aux informations de sécurité GoSecure TitanMC (SIEM)

Détection et réponse des boîtes de messagerie GoSecure TitanMC (IDR)

Intelligence GoSecure TitanMC

Notre SOC

Défense proactive, 24h/24, 7j/7